Moving Image Department #7: Brian Eno, Loď, účinkuje Jan Nálevka

16. 3. 2017 - 9. 9. 2017

Výstavy

The 7th chapter of the Moving Image Department goes astray. Provocatively and exclusively, its centerpiece is occupied by no moving image, its absence, a visual void and a suspense of motion (picture). Instead, the 7th chapter of the Moving Image Department acts as a moving image generator itself, proposing an imaginary picture – a phantom – as a construction of sound and light.

The groundbreaking work of a legend of experimental music, Brian Eno has been for decades a powerful vehicle of imagination and ambiance, able to enchant the senses beyond the confines of reason and emotion. His recent 25th-solo-album-cum-multi-channel-three-dimensional-sound-installation, “The Ship” (2016) has been described by its author as a sort of "musical novel" – a loose story collage inspired by the Titanic sinking, World War I and random throwaway lines from emails and Eno’s own (failed) writing, all-in-all remastered by an algorithmic text generator. Its 21-minute title track has been compared by a critic to “a theatre of the mind”, composed of sonar blips, harbor bells and human voices weaving in and out of a luminous soundscape that evokes an orchestra. "Humankind seems to teeter between hubris and paranoia," Eno writes, and "The Ship" captures that anxiety, evoked by a reference to two catastrophic events a century ago. The three-part "Fickle Sun” is an eulogy to the waves of young soldiers left to rot and "turn back to clay" in a muddy Belgian battlefield while a cover of the 1969 Velvet Underground's anthemic "I'm Set Free" closes the soundtrack and leaves the listener with Lou Reed’s lyrics "I'm set free to find a new illusion.”

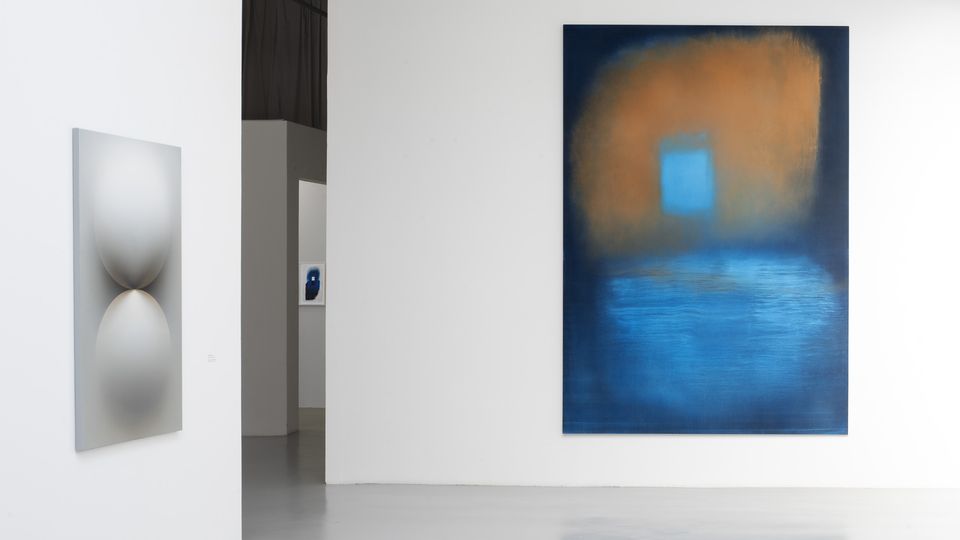

“The Ship” finds Eno combining ambience with his own voice for the first time in composing what may be described and experienced as a spatial song. "It was all pretty much normal until, at a certain point, I realized that I could sing the lowest note of the piece, which is a very low C," says Eno. "Well, I've never been able to sing low C before. As you get older, you know, your voice drops, so you sort of gain a semi-tone at the bottom and lose about six at the top every year. That's what's happened to me. So I've suddenly got this new, low voice I can sing with, and I just started singing with that piece. And so it was the first time I thought, "Oh, what about making a song that you could walk around inside?” As an installation, “The Ship” is an all-immersive sonic environment, composed of several vintage loudspeakers placed on monolithic structures, and distributed across a dimly illuminated room. The atmosphere is powerful yet intimate. The voices remastered by a computer program called “Vocal Transformer” receive “a sort of muted ghostliness” which imbues the space with uncanny flair and hypnotic feeling, providing a strong cinematic experience and influencing the listening behavior, consequently turning the listener into an active “viewer” and participant.

Additionally, the exhibition includes Brian Eno’s seminal “14 Video Paintings”, comprised of “Thursday Afternoon” and “Mistaken Memories of Mediaevil Manhattan”: the two works that are to the video format what Eno’s audio pieces were to music; ambient musings on the nature of the medium. Both, they tackle the age-old art subjects of a (female) nude and a (city) landscape in a genre of painterly portraiture. Slowly evolving "video paintings" of "Thursday Afternoon" focus on the human figure in a series of intimate tableaux showcasing the close-ups of the face and the nude body in different postures and poses of Eno’s close friend, actress and photographer Christine Alicino, accompanied by a beautiful single hour-long title piano track. The sequence of hypnotically unfolding images of "Mistaken Memories" (often considered the first ambient film) features Manhattan skyline, filmed from the artist’s NYC’s thirteenth-floor apartment, with clouds moving overhead in an oneiric mode, set to tracks from “Music for Airports” and “On Land”. As such, “14 Video Paintings” is both a nostalgic diary and a melancholic travelogue. The low-grade equipment give the images a hazy, impressionistic quality; these are moving paintings, shifting slightly and slowly, fading in an out. Lack of a tripod meant filming with the camera lying on its side so the tape had to be re-viewed with a television monitor also turned on its side, or the viewer lie on his/her side. Such “vertical orientation” was also calculated to recontextualize the television set and to subliminally shift the way the video image represents recognizable realities. Eno himself was aware of the newness of what he was doing. "I was delighted to find this other way of using video because at last here's video which draws from another source, which is painting … I call them "video paintings" because if you say to people "I make videos", they think of Sting's new rock video or some really boring, grimy "Video Art". It's just a way of saying "I make videos that don't move very fast"." Eno also believes that his music has a strong relationship with painting and cites a long list of artists among his influences, including Kitaj, Mondrian, Kandinsky and Matisse. “I like the idea of my music being treated like sound pictures. You don't sit and stare at paintings for three minutes, you can turn your back. Painters are not insulted by lack of attention, why should composers be?”

Thus Eno reflects upon the nature of his video experiment as articulated in the inset in Eno's albumvideo "Thursday Afternoon” (1984): “These pieces represent a response to what is presently the most interesting challenge of video: how does one make something that can be seen again and again in the way that a gramophone record can be listened to repeatedly? I feel that video makers have generally addressed this issue with very little success: their work has been conceived within the aesthetic frame of cinema and television (an aesthetic that presupposes a very limited number of viewings) but then packaged and presented in a format that clearly intends multiple viewings, the tape or disc … Unfortunately, the cinematic heritage seems inimical to the idea of multiple-view video tapes or discs. It relies heavily for its impact on a dramatic momentum, which is sustained by frequent scene changes, fast editing and the narrative development of the plot. As a result, being in some way a function of surprise, this impact is eroded by repeated viewings. The usual response to this problem has been to load the video with more scene-changes, faster edits, stranger camera angles and more exotic special effects, in short, more surprises – presumably, in the hope of delaying the inevitable decline in interest in the work as it becomes more familiar. This is the condition of pop-video, and it has almost nowhere left to go in this direction. So long as video is regarded only as an extension of film or television, increasing hysteria and exoticism is its most likely future. Our background as television viewers has conditioned us to expect that things on screens change dramatically and in a significant temporal sequence, and has therefore reinforced a rigid relationship between viewer and screen – you sit still and it moves. I am interested in a type of work which does not necessarily suggest this relationship: a more steady-state image-based work which one can look at and walk away from as one would from a painting: it sits still and you move”.

Describing himself as a non-musician who advocates the methodology “theory over practice”, Brian Eno (1948) is best known for his pioneering work in ambient and electronic music as a musician, composer, record producer, singer, and visual artist. For more than four decades, beginning with 1975’s “Discreet Music”, Brian Eno's solo works have presented a universe of sound frozen in slow motion, melting to reveal and revel in new layers of dreamlike impressions. Eno redefined minimalism with his 1978 album “Ambient 1: Music for Airports” and on nearly two-dozen solo offerings that followed. Eno graduated Colchester Institute art school in Essex, England, taking inspiration from minimalist painting. During that time, he also gained experience in playing and making music through teaching sessions held in the adjacent music school. He joined the band Roxy Music as synthesizer player in the early 1970s and collaborated with other musicians since then, including Robert Fripp (on albums “No Pussyfooting” and “Evening Star”), and David Bowie (on the seminal "Berlin Trilogy”). Eno helped popularize the American band Devo and the punk-influenced "No Wave" genre. He produced and performed on three albums by Talking Heads, including “Remain in Light” (1980), and produced seven albums for U2, including “The Joshua Tree” (1987). Eno has also worked on records by James, Laurie Anderson, Coldplay, Paul Simon, Grace Jones, James Blake and Slowdive, among others.